So many people, including me, have talked about how glyphosate tolerant crops allowed replacement of more toxic herbicides. That was certainly true for a while, but that trend seems to be over, according to this “largest ever” study of the environmental impacts of GE crops: Genetically engineered crops and pesticide use in U.S. maize and soybeans (open access). You can also view the press release: Largest-ever study reveals environmental impact of genetically modified crops.

To put things in context, let’s look at adoption of GE crops. There has been a steady trend of increasing adoption and then market saturation. Nothing new there, but it does set the stage for the conclusions of the study: 89% of US corn (aka maize) and cotton and 94% of US soybeans are herbicide tolerant.

Some previous studies have looked at herbicide “pounds of active ingredient” without considering the toxicity of the herbicides. The researchers of this paper factored in EIQ (Environmental Impact Quotient) which considers toxicity of pesticides. EIQ is not a perfect method of assessing pesticides, but is much more useful than pounds.

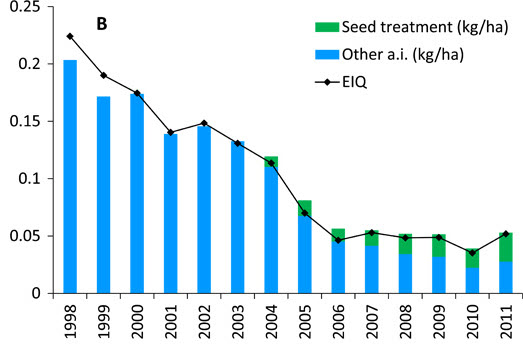

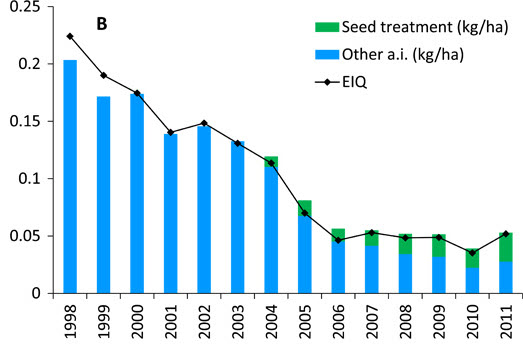

The first conclusion that sticks out in this study is a confirmation that insect resistant GE crops have been and continue to be positive for the environment. This has been shown again and again. This image from the paper shows a clear decreasing trend of insecticide use in corn, though that trend may be reversing in 2011, the latest years in this dataset.

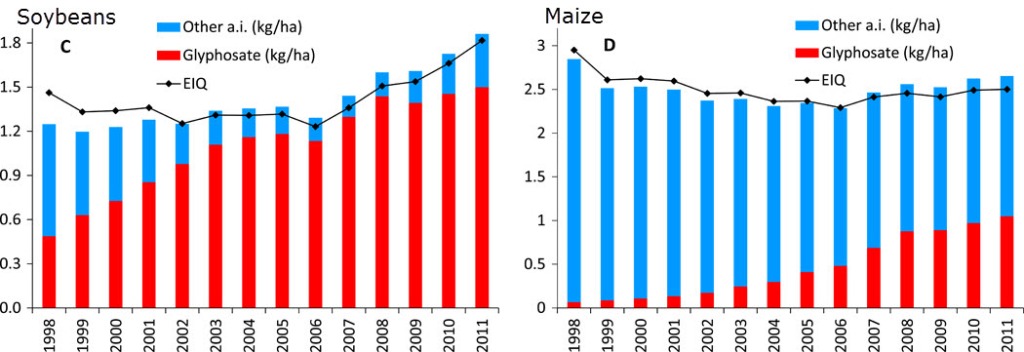

The herbicide story is a bit more complicated. This set of images (adapted from the paper) shows total herbicide use in soybeans and maize, with the black lines showing active ingredients weighted by EIQ. For soybeans (left) the total EIQ of herbicides used decreased slightly then started increasing in 2006. For maize (right) the total EIQ of herbicides used decreased slightly then leveled off.

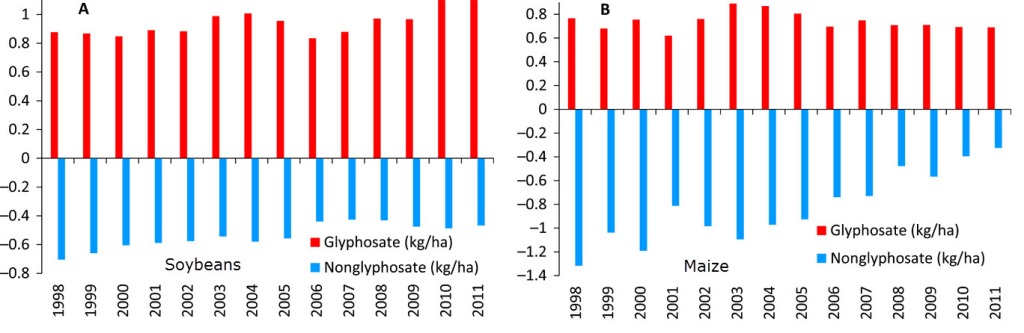

This set of images has the same information as the pair above, but provides a visual contrast between total glyphosate (red, top) and other herbicide use (blue, bottom). For soybeans (left) non-glyphosate herbicides seem to be staying constant or even increasing slightly as use of glyphosate increases from 2006 to 2011.For maize (right) there’s a decreasing trend in non-glyphosate herbicides that continues into 2011, the most recent year in this dataset.

One mitigating factor could be number of acres. There is an increasing number of acres of soybean planted from 1998-2011. However, there was a dip in planted acres of soybeans in 2007 and the herbicides used didn’t dip correspondingly. The planted acres of corn also increased during this time, but the total amount of herbicides used on corn has remained pretty steady, indicating that farmers are growing more corn with less herbicides.

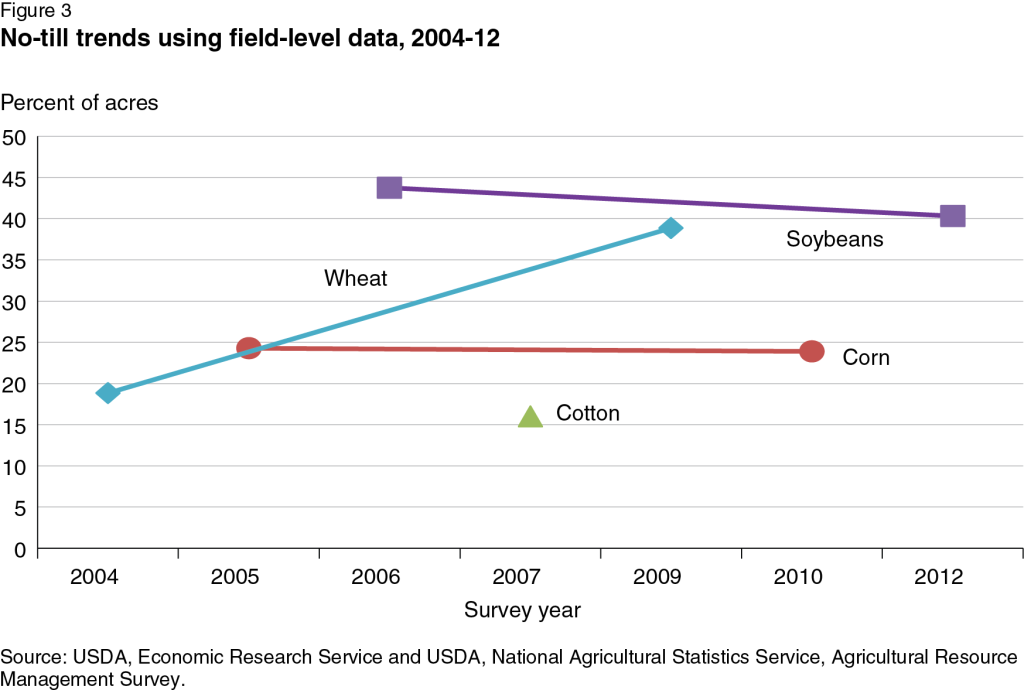

Another issue barely touched on by these researchers is tillage. Herbicide tolerant GE crops have helped some farmers to adopt no-till or low-till farming (tilling is used to kill weeds, so herbicide can replace tillage in some situations). And reducing tillage definitely has a positive impact on the environment. However, no-till adoption is lower than you’d expect. According to the 2015 USDA report Conservation-Practice Adoption Rates Vary Widely by Crop and Region, no-till/strip-till was used in 31% of corn, 46% of soybeans, 33% of cotton, and 43% of wheat in 2010 and 2011. If herbicide tolerance traits were very effective in reducing tillage, we should expect higher numbers in corn and cotton, and we should expect increasing trends in no-till use, not decreasing.

There is a non-GE herbicide tolerance trait called Clearfield in wheat (also in canola, sunflower, rice, and lentil), so that may account for the high percentage and increasing trend of reduced till wheat, but I wasn’t able to find how much of US wheat is Clearfield. It would be interesting to see what the environmental impacts have been of the Clearfield trait, and compare impacts of non-GE herbicide tolerance to GE herbicide tolerance. I suspect the impacts would be similar, though we’d have to consider that the Clearfield system works with imazamox herbicide, which has a slightly higher EIQ (19.52 for imazamox compared to 15.33 for glyphosate).

Anyway, let’s look at the main findings of the paper: “For all soybean herbicides, corn herbicides, and maize insecticides, the farmworker and consumer components were lower on account of GE variety adoption. For the ecology component, maize herbicides and insecticides were improved by GE adoption, but for soybean herbicides, GE adoption had a detrimental effect “

In other words, GE has overall had a positive effect, but in the case of GE herbicide tolerant soybeans, it has actually had a negative environmental impact. Not because of glyphosate, but because of other herbicides used with glyphosate. Now, if GE herbicide tolerant soy had never existed, more toxic herbicides would have been used anyway so overall there has still been a net positive. But based on this paper, claims about environmental benefits of GE herbicide tolerant soybeans are are overstated, especially when you consider that the claims about tillage may be exaggerated as well.

The authors of this study propose that the increases in non-glyphosate herbicide use in soybean is due in part to glyphosate resistant weeds. It may only be a matter of time before non-glyphosate herbicide use increases in maize as well. Glyphosate is too important of an agricultural tool to lose, so we need to take steps to reduce weed resistance. Ironically, the best way to do that may be spraying more herbicides.

To end this post on a positive note, let’s look again at the chart showing insecticide use in corn. While isolated examples of insect resistance to Bt corn have been found, in the US at least, that resistance is not widespread enough to warrant increasing use of insecticides, at least up to 2011, the last year found in this dataset.

- Comment

- Reblog

-

Subscribe

Subscribed

Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.

Useful summary, but the images marked A and B need a better explanation to be undestood.

Taking A and 1998, am I correct in understanding that a GE adopter used on average 0.9 kg more glyphosate and 0.7 kg less non-glyphosate herbicides than the non-GE adopter?

LikeLike

I think the answer to your question is yes.

Prior to RR soybeans most growers used a 2 pass system of a pre-emerge herbicide followed by a post application like Pursuit. Glyphosate was so effective and the price got to the point that growers got away from the pre-emerge pass and relied on 1-2 post trips of glyphosate. We are now seeing soybean growers go back to multiply modes of action and pre-emergent herbicides are becoming a standard in glyphosate resistant weed areas. But in those areas the weed challenges can be significant enough that a pre-emerge and 2 passes of glyphosate are now the norm. So now soybean growers are looking at 3 passes (up to 4-5 in serve weed resistant fields) vs. 2 passes as in the past. The end result can be an increase of non-gly herbicides and increased gly applications also.

LikeLike

If the soy farmers used the older method of a 2 pass system followed by pursuit, wouldn’t this method lead to pre emerg resistance and Pursuit resistance. leading to more Pursuit being used. with the bonus of limiting rotation choice for farmers.

LikeLike

Once gly came on the market the whole game changed in the soybean herbicide business. Am Cy was a power house with Prowl and Pursuit. It was costing $40-50/acre in the 90’s for a soybean weed control program. They literately disappeared as a major corporation within about 5 years because they could not compete with the cost and control of gly. Growers abandoned a traditional 2 pass system and when to gly. I would throw out this where a lot of our resistant issue began. Gly was cheap, easy, and unfortunately just one mode of action. If we would have continued with multiply modes in soybeans like with we did with corn resistant issues would have been slower to raise their ugly head.

LikeLike

What about the carryover issues with Prowl and Pursuit?

The great thing about glyphosate, is that there is no carryover issues.

Giving soy farmers more choice.

I do agree that Glyphosate is suffering from its own success and more modes of action should have been used.

LikeLike

Agree, gly is an outstanding herbicide with no carryover issues (wish we could get the gly haters to understand that). We just became too reliant on one method.

LikeLike

outstanding herbicide with no carryover issues (wish we could get the gly haters to understand that).

But the really don’t care about the issue. All they know is Monsanto is a big meanie and they are trying to take over the world.. (with seeds, most likely the most insane world domination method ever conceived of). Like really, if you wanted to take over the world, would you do it with seeds?

We just became too reliant on one method.

Yes agreed. I remember when I was a kid seeing fields full of Canadian thistle, Today I rarely see even a single plant.

LikeLike

You make some very good points.

Around the time the RR1 soybeans were taking off (’98), Monsanto and Cyanamid were going to merge. I don’t recall the reason for the merger not happening, but BASF eventually got Cyanamid’s crop protection unit. There were all kinds of mergers right around that time, mostly drug companies combining and seed/biotech businesses just along for the ride. It wasn’t long after this that Pharmacia spun off Monsanto as just a crop biotech company, sort of a redheaded step child in a way.

It’s interesting to ponder whether there would have been earlier emphasis (outside of university and extension agronomists and weed scientists) on the use of multiple modes of herbicides had that Monsanto-Cyanamid merger gone through though…

LikeLike

I remember the days of chemical reps with their big expense accounts willing to take a group of customers to any gentlemens establishment they wanted.

Ahh… the good ol’ days…

LikeLike

The answer to your question is we will never know if resistance to Prowl and Pursuit would have occurred in the same time frame as gly since farmers just abandoned those costly 2 pass programs.

LikeLike

Points to the importance of stewardship and also, resistance management techniques can be written into labels. Have dealt with this for a number of fungicides; resistance management is possible, but it requires a bit of self control and a long-term view.

LikeLike

Herbicide weight has nothing to do with effectiveness. I think the older soy herbicide Pursuit, the applications rate was 2 oz per acre and glyphosate is 16.

Pursuit is far more environmentally toxic than glyphosate.

LikeLike

Yes, and Serralini wins court cases…….

LikeLike

And what does that have to do with herbicide use?

LikeLike

Thanks for the question. I edited the text a bit to make it more clear that the two sets of red and blue graphs are showing the same data. It’s showing the change in herbicide use over time. As far as I can tell from reading the paper, the data is just of pesticide use in the US. It doesn’t separate out GE vs non-GE crops. Since GE crops make up such a huge percentage of the total though, it’s probably a fairly accurate representation of the pesticides used on GE crops.

LikeLike

“EIQ is not a perfect method of assessing pesticides, but is much more useful than pounds.”

Perhaps not: http://weedcontrolfreaks.com/2016/09/is-the-environmental-impact-quotient-eiq-better-than-nothing/

LikeLike

“Pounds” wasn’t mentioned in your reference. “Pounds” of different chemicals is only useful for misinformation and shipping costs. Nothing else.

LikeLike

The author covered that by linking to another of his posts on the subject rather than repeating himself.

“This ‘pounds on the ground’ approach ignores toxicity and exposure potential, and therefore tells us nothing about actual risk.”

http://weedcontrolfreaks.com/2015/07/an-evaluation-of-the-environmental-impact-quotient-eiq/

LikeLike

Which agrees with my statement. I’m not defending EIQ. I’m saying “pounds on the ground” is worse than worthless unless comparing the same chemical.

LikeLike

Yes, that is a good post by Dr. Kniss. I get what he’s saying but at least the EIQ tries to do something about the toxicity question. Pounds is the worst because the least toxic chemicals may be applied a higher rates, giving a totally wrong impression of the impacts. I’d like to see Dr. Kniss or some of his weed science colleagues update/improve upon the EIQ with a new measure, but until then I think the authors of this paper used the tool they had at hand. I didn’t go into detail about it in this post, but I really liked how these authors looked at the different aspects of the EIQ (such as farmworker safety).

LikeLike

What do you think of the eco-efficiency concept he proposes as a possible alternative? https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eco-efficiency

As Dr. Kniss points out, random numbers fed into EIQ can be used to support the same conclusions. That should certainly give one pause. Just because something is the best one has does not make it good enough. It’s like saying ones calculations are totally wrong, but they are the best they have, so they should use them anyway. Gives one the false sense that their data actually supports their claims when what they should be doing is not making any claims at all until a valid analysis can be done.

LikeLike

There is a fact I didn’t see mentioned: We don’t know what 2016 would have been like if GE had never been discovered (or is that an invention?).

No matter what farming method is used, there will be pest adaptation over time.

LikeLike

there will be pest adaptation over time.

Hmmm I don’t know about that? Has anyone studied if “Sharks with lasers” cause resistance? how about Napalm? Depleted uranium? How about using a M1A1 tank as a tractor? Scud missiles for tillage?

sorry I have been watching far too many war videos lately.

LikeLike

“No matter what farming method is used, there will be pest adaptation over time.”

True but that is not the point. I recall Nate Johnson pointing to some early Monsanto RR GM literature that was way too optimistic about the impact of RR GM crops on the development of glyphosate resistance. The company and the government should have been draconian in forcing farmers to adopt best practice to slow down resistance. Moreover as per the Weeds Control link in the OP, it would have been far more sensible if the regulators had insisted on stacked herbicide resistant traits before approving the first GMs with herbicide resistance. Monsanto and farmers have to take its share of the blame for this as well.

As you may recall, I am 100% on board the GM train but this is a clusterf#ck that involves “known knowns” (if I may borrow Rumsfeld’s terminology) so it really is inexcusable.

LikeLike

There was a lot of concern about stacked herbicide traits at the time. One of the issues being how do you control the volunteers.

If Monsanto hadn’t believed their own press about the indomitability of glyphosate at the time, perhaps they might have moved more quickly when resistance happened. It wasn’t as if they hadn’t any warning from Australia.

Forcing farmers to adopt best practice is a difficult thing as best practice is often in the eye of the beholder and varies from place to place. Regulation of best practice would be unhelpful. I think it better to treat farmers as intelligent adults, you give them the information, explain the pitfalls and let them work out the best way to use the tools. The trouble arises when one corner is saying there are no pitfalls.

LikeLike

Chris, if adults behaved like “intelligent adults” we could sack the police force and close down half of our hospital emergency departments. But life isn’t like that. I think glyphosate is as important as a class of anti-biotics and it should always have been strictly regulated to maximise its useful life. But where one stands on issues like this is partly about ones political philosophy, and I admit to being a big government pinko nanny stater 😉

BTW, IIRC, the first case of glyphosate resistance was annual ryegrass in Oz and it happened because farmers not behaving like intelligent adults just kept spraying glyphosate over and over again year in year out in the same paddocks for the same crops.

If I got that wrong I’m happy to be corrected.

Thanks for the info on concerns about stacked herbicide traits. I was not aware of that.

LikeLike

You’re right. I remember Monsanto insisting that in the 20 yers prior, there were no know resistant weeds and that “dead weeds don’t breed resistance”. But that was opposite of what universities were recommending at the same time.

The conveninence, price & effectiveness made people really want to believe Monsanto on that issue.

LikeLike

Yep, it is understandable that companies like Monsanto want to get an income from their huge investments as soon as possible. I applaud them for their investments and can excuse them for having a Panglossian outlook, but the Nanny State (imho) needs to be long sighted and regulate and enforce good practice.

LikeLike

I detest the nanny state, Cap’n. I would prefer regulators at the time should have come down hard on Monsanto if they made spurious claims for their product. Public service educators ought to have countered any such deceptive advertising. I vaguely recall statements (rumors or wive’s tales really) floating around at the time to the effect there could be no resistance to RoundUp. Most of us disbelieved them then, just as we would now. Not surprisingly, a lot of us used the product sensibly and have seen no incidence of resistant weeds as a result. Sure, some folks abused the product, just as they routinely abuse everything else from motor vehicles to Budwieser beer and, not surprisingly, those clowns precipitated resistant weeds. Your nanny state has struggled to tame these obstreperous types, regardless of how forcefully it crushes and smothers the rest of us. Please, Cap’n, do not invoke more nanny statism on my already beleaguered entrepreneurial arse.

LikeLike

The only legislative solution I can see being useful is more funding for extension programs.

Look at Palmer Amaranth, for instance. It’s the biggest weed threat to agriculture at this time, but it’s not even on the federal invasive species list, nor on my state’s (IA) list.

LikeLike

In our area we have had consolidation of local offices and reductions in staff. They are operating on a shoestring budget and skeleton crew.

With limited resources and personnel they have fallen behind the tech and information curve compared to private industry. Growers do not see extension as a place to get Ag questions answered.

I would like to see extention regain their status as a key informational resource for the Ag community, but unfortunately I think that ship has sailed.

LikeLike

That’s a real shame. We have a really good program here – good knowledgeable people and they earn their paychecks IMO. Most if not all of the field agronomists are on twitter, etc., so you can tweet a picture of a weed and get an i.d. fast. Plus good support on entomology, soil science, etc.

LikeLike

You’re lucky that way Joe. I hear Iowa is the exception when it comes to extension. Ohio, Penna, Illinois and Wisc aren’t too bad, I guess Mich is OK, but as agboy says, they all have declined a lot and aren’t keeping up. I hear in New England the extension services are a complete farce, spending all their effort and budgets on urban issues, gardening, social services and barely lip service to commercial agriculture. A buddy tells me for years now the New York extension has been encouraging struggling farms to “diversify”, but is most fully ramped up to smooth a farm’s exit out of business — they’ve actually given up! Anyway, extension is about the last place I would go for actionable intelligence on a weed/herbicide question. We have access to some very talented crop consultants. Given a free hand they can be dangerous but if you manage ’em carefully (like anything else) you can achieve quality results and everybody can make a little money.

LikeLike

There are good independent agronomists here, too. And actually, the technical services people from the big ag companies can be really good resources. You just have to get past the level of the “sales agronomist” people to get to them. That’s probably a little unfair to the sales agronomists, but they are always in the position of having to portray their product(s) in the best possible light. It’s not nearly as bad as the old joke, “How can you tell if a salesman is lying? His lips are moving”.

Anywho, if I were king, we’d be putting a bunch more money into all forms/disciplines of research, a bunch more into ag extension and less into endless money pits like the F-35 program. We’re into that fiasco for a cool $1 trillion with no end in sight, ugh.

LikeLike

Yep. Some well placed budgets in ag research and applied science at our land grant universities could be profitably invested for commercial agriculture and food consumers. University research and extension in cutting edge agriculture once was the gold standard but it’s been a long dry spell with those characters.

LikeLike

I agree, but I also think it’s important to fund research that doesn’t necessarily have an obvious near-term commercial application.

LikeLike

more funding for extension programs.

Nailed it. Instead, these programs are falling behind.

I also see benefits of the farmers be the actual owners of the land, but I wonder how realistic that is.

LikeLike

In IA, it’s about evenly split between owned and leased land. There’s one farm management company I can think of that is doing a decent job of educating landlords about conservation tillage, etc. If management companies and the landlords themselves would take an active role in resistance management, it would definitely help. I’m not exactly sure off the top of my head how you’d write meaningful terms into a farm lease, though.

With the low-to-no margins the last couple of years, I don’t see that split changing anytime soon.

LikeLike

I sort of agree with you, JRS, about ownership but we’ve always treated rented ground the same as we treat owned ground, especially when it comes to weeds and herbicide protocols. I will admit a reluctance to invest a crazy bunch of money in topping off soil pH, clearing up hedge rows or tiling, that sort of thing if we can’t get a long term lease. Still, it isn’t like we aim to mine the place out, or anything like that.

As far as weeds and herbicides go, prior to RoundUp we actually were reluctant to rent or even do custom work on ground that was badly weed infested. When glyphosate came along we finally had a safe effective affordable tool to burn the weeds back & gradually deplete seedbanks out of well located rental farms. We cleared up a few places under lease with option to purchase and ended up picking a couple of real nice farms that complement our holdings. No regrets, no environmental damage.

LikeLike

Australia has traditionally had a bigger and more interventionist government than America and I’m a pinko lefty, FWAD. Please forgive my sins 😉

LikeLike

I’m involved in Nutrient Management Plans and regulated by government agencies. They have horribly stupid ideas that are counterproductive and wasteful.

Herbicide application best pract varies across just my farm, and take specialized local knowledge. Most farmers I know will spend a little more to avoid resistance if they’re properly educated.

I do think application licenses should be far more strict.

LikeLike

I’ll agree that applicator certification (at least the program here) could be improved, but I’m not convinced it would be a very effective way to convey information about herbicide resistance.

Part of the problem I see, though, is for operations that hire out their spraying – like to the local coop. The coop wants to send out a crew and spray one product everywhere, they’ll balk at a request to spray something other than say Cobra on soybeans. That kind of stuff doesn’t help our cause.

LikeLike

Heh, not only are some of the nutrient management requirements stupid, counterproductive and wasteful, but I’ve noticed a distinct tendency for the most stupid implementations to be the most permanent and most expensive. And , boy, are they expensive!

Some of the implementations benefit our business (and I swear that’s a mistake by the CAFO overlords when it happens), and those most often are not terribly expensive at all (we can even find a payback argument in the best ones).

In fairness, we’ve benefited by our nutrient management program — the practical part — and we’ve humored the bureaucratic BS…with clenched teeth sometimes, but so far we’ve humored it.

LikeLike

That’s definitely true. Pests adapt, even to totally non-chemical control methods like tillage and crop-rotation. I think studies like this tell us that GE crops have had a positive impact on the environment overall, but caution us to be careful with the tools we have (and hopefully the new tools that will come along as well).

LikeLike

OTHER 2016 SCIENTIFIC PAPERS ADDRESS THESE ISSUES with some supplementary information.

I read with interest the paper “Environmental impacts of GE crops” as well as the comments.

Another scientific paper (at least) published in early 2016 deals with these issues, it is mainly devoted to GM glyphosate-tolerant soybean in the USA.

It deals particularly with the trends in herbicide and glyphosate use on GM herbicide-tolerant crops in the USA, the spread of glyphosate-resistant weeds in the USA and worldwide, and notably their impact.

The article also deals with some causes of the development of glyphosate-resistant weeds, as well as with some important consequences such as how the involved stakeholders – industry, farmers, weed scientists – are coping with this issue.

Please find here the reference:

Bonny S. 2016. Genetically Modified Herbicide-Tolerant Crops, Weeds, and

Herbicides: Overview and impact. Environmental Management 57 (1), pp 31–48.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00267-015-0589-7

I hope that this information may be useful.

LikeLike

SOME SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION on this topic in ANOTHER 2016 SCIENTIFIC PAPER.

I read with interest the paper “Environmental impacts of GE crops” as well as the comments.

Another scientific paper (at least) published in January 2016 deals with these issues, it is mainly devoted to GM glyphosate-tolerant soybean in the USA.

It deals particularly with the trends in herbicide and glyphosate use on GM herbicide-tolerant crops in the USA, the spread of glyphosate-resistant weeds in the USA and worldwide, and notably their impact.

The article also deals with some causes of the development of glyphosate-resistant weeds, as well as with some important consequences such as how the involved stakeholders – industry, farmers, weed scientists – are coping with this issue.

Please find here the reference:

Bonny S. 2016. Genetically Modified Herbicide-Tolerant Crops, Weeds, and Herbicides: Overview and impact. Environmental Management 57 (1), pp 31–48.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00267-015-0589-7

http://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00267-015-0589-7

LikeLike

Hi Bonnie! How familiar are you with evaluating scientific papers?

It really seems like you’re not at all familiar.

Here’s a tip: When someone provides you with a reference, look at the title first. Then look at the authors. Then read the abstract. Then read the citations.

In this case, the citations raise a red flag, dear. Oh, and the fact that this is a single-author paper.

But thanks for sharing anyway. I’m sure you’ll get participation points as a member of the Maharishi cult in good standing.

LikeLike